Kehinde Wiley

Credit: kehindewiley.com

I first came across Kehinde Wiley’s works from a google search for black painters. To say I fell in love at first sight is an understatement. Wiley’s world is colorful, stoic, and innovative.

By painting contemporary black figures in classic art-historical poses against colorful backgrounds, Mr. Wiley unapologetically lets the viewer know that black people are here, regal, and have a rightful place in the artistic firmament. But Kehinde’s success story is the exception, and not the rule, in the world of fine art where black faces are often unwelcome and underrepresented.

Wiley is probably best known for painting Barack Obama’s presidential portrait for the National Portrait gallery. He is the first black artist to ever paint an official presidential portrait. His accomplishments are too many to list so I’m not going to get into detail about his mastery of classical art, his nod to the Roccoco style, or the fact that he earned an MFA from Yale; there are several art historians, gatekeepers, & journalists who’ve already told that story which brings me to the “gatekeepers.”

While I love reading about art and learning more about a particular artist, most art critics, museumgoers, and curators don’t look like me and it is a reminder that it’s another part of society that black people have been excluded from. It is a reminder to stay in our place & exactly what is that place? In a USA Today article titled “Art so white: Black artists want representation (beyond slavery) in the Met, National Gallery,” Jennifer Tosh, founder of Black Heritage Tours in New York and Amsterdam, says

“people of color have been excluded from the ranks of fine artists in America and viewed only as objects of observation. You can certainly connect it to structural and institutional racism. There’s been a systemic history of race and racism as its byproduct that has situated black people in a certain way."

If you look at classical pieces of art from the “old masters” displayed in museums across America, black faces are largely absent from these works of art and when they are present they are often depicted as servants, savages, slaves, or in a subservient position to their white counterparts. Dutch painter, Jan Steen’s oil painting titled “Fantasy Interior with Jan Steen and the Family of Gerrit Schouten," painted ca. 1659-60, is a prime example of the depiction of black people in a subservient role to whites.

This depiction of black people that has persisted throughout the centuries in American art is more than happenstance; It is systemic and deliberate. Curators, critics, and patrons of art have helped to shape the image of blackness in America, preserve white supremacy. Kehinde Wiley is upsetting the status quo & doing it with black excellence.

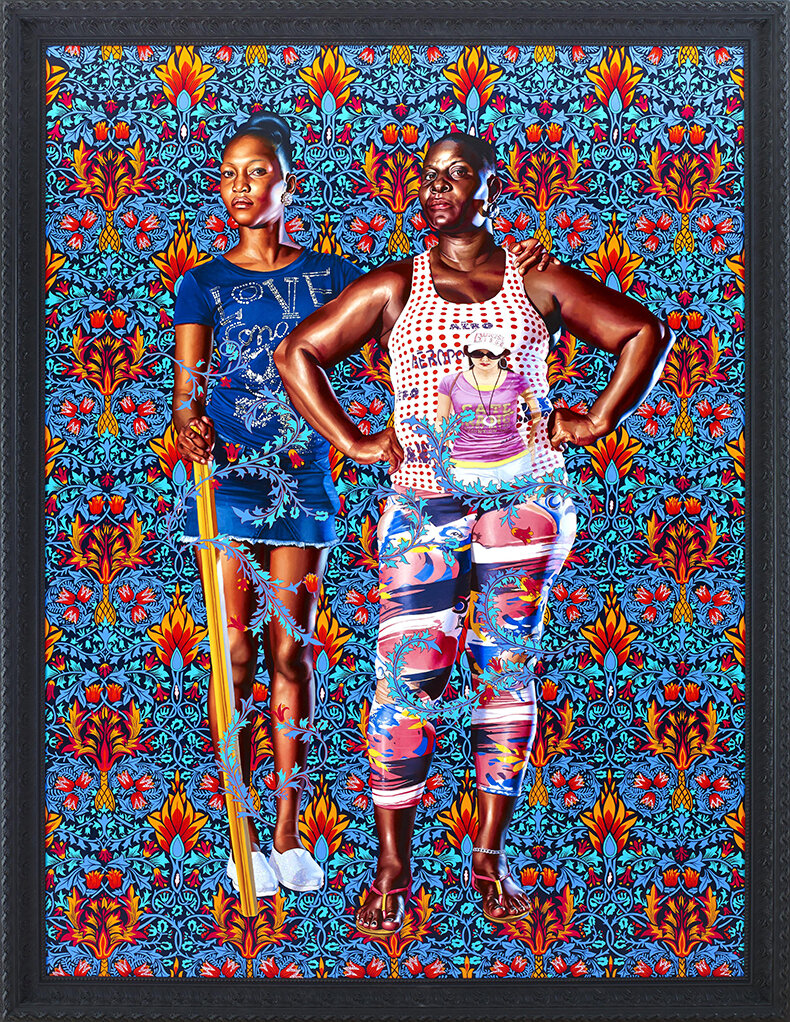

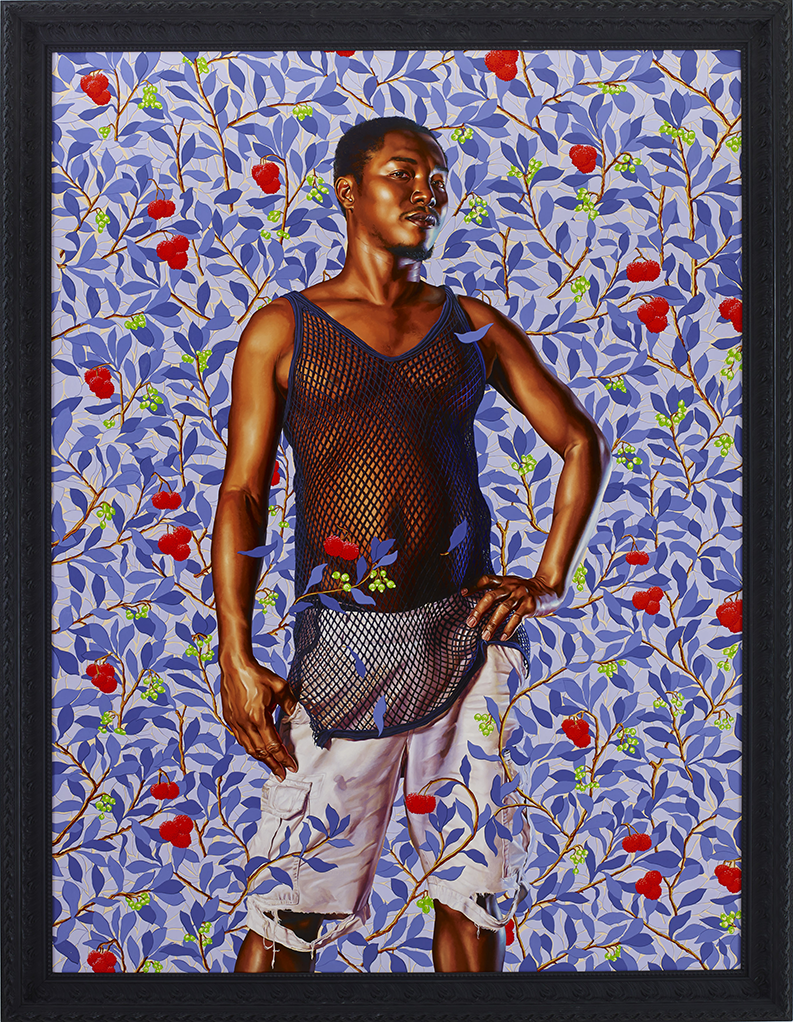

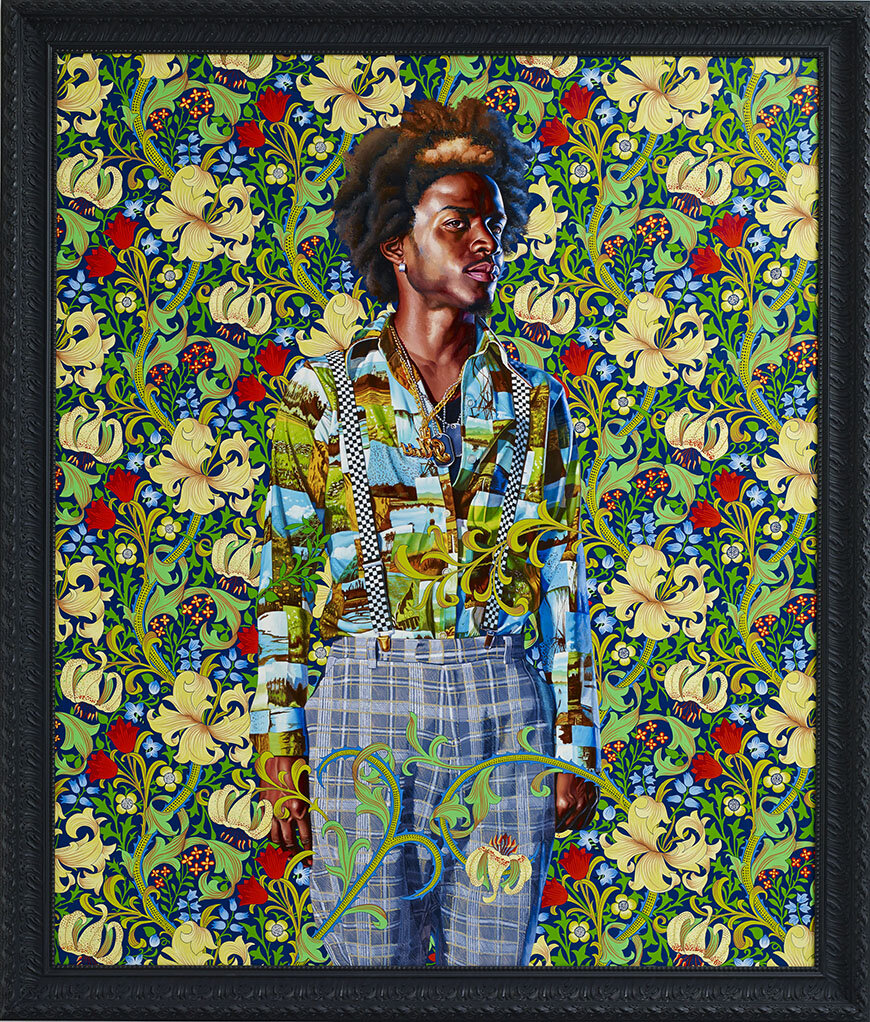

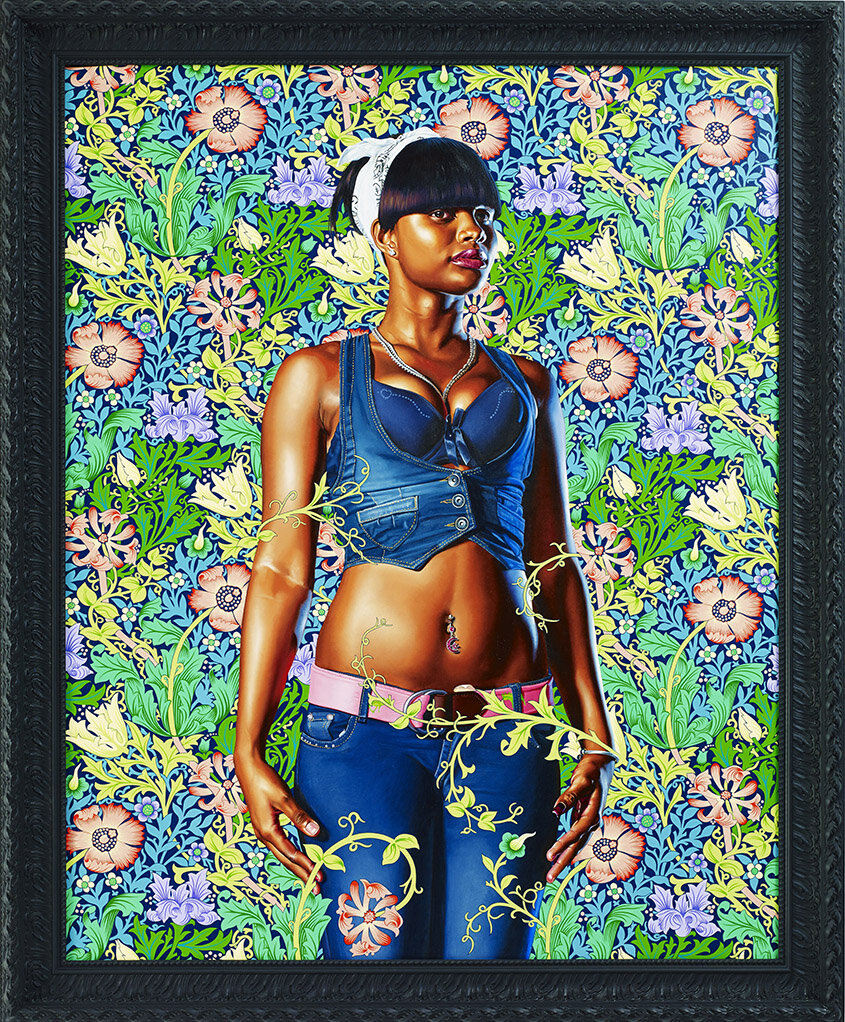

Jamaica

The World Stage

Credit: KehindeWiley.com

From top left:

“Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness,” 2013. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

“Three Boys,” 2013. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

“Portrait of John and George Soane,” 2013. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

“John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester” 2013. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

“Portrait of James Hamilton, Earl of Arran,” 2013. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

“China Samantha Nash,” 2013. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

“Mary, comforter of the Afflicted I,” 2016. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

Credit: kehindewiley.com

In 2015, New Orleans based artist Ti-Rock Moore exhibited a sculpture of teenager Michael Brown lying face down surrounded by police tape. The piece was titled “Angelitos Negros.” Brown’s father called Moore’s Chicago exhibit of his son disgusting and stated that the piece was “disrespectful and inappropriate.”

Moore’s piece sold for $5,500.

In 2019 Chaédria LaBouvier became the first black curator in the in the 80 year history of the Guggenheim Museum but that position was short lived. Her debut exhibit “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement’: The Untold Story,” was a timely exhibit and although Basquiat died over 32 years ago at the age of 27, the exhibit couldn’t have been more apt given the current zeitgeist of police brutality and the BLM Movement.

But the accomplishment was a bittersweet one for Chaédria who, as the curator of a hugely successful and groundbreaking exhibit, wasn’t even invited to be a part of a panel about her work. The treatment of LaBouvier is reminiscent of Ellison’s Invisible man and the commodification of blackness that is inextricably intertwined in the fabric of American life. LaBouvier called her time at the Guggenheim “the most racist professional experience of her life.”

“Judith and Holforenes,” 2012. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

Credit: kehindewiley.com

So what does all this have to do with Kehinde Wiley? Wiley is one of many in the black art community who is changing the narrative either on the canvas or behind the scenes. He is a step in the direction of equality and representation for myself, black people who love art, and future generations of black people who study art and pursue careers in the field but have never seen themselves represented on the canvas or behind the scenes in the art world.

White kids & white people in America grow up being exposed to the full spectrum of whiteness. They are allowed to be everything from white-trash, president, executive, lawyer, doctor, scientist, mathematician, painter, poor, wealthy, beautiful, ugly, as subjects of great work of arts, and the list goes on. White kids get to play with water pistols, wear hoodies, and go to the grocery store to buy candy without being shot. There is no limit to their dreams and aspirations. Even poor white kids with limited resources get to turn on the television, open a book or magazine and see a million different versions of themselves. We want those same freedoms for our kids, for us.

“The Two Sisters,” 2012. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

Credit: kehindewiley.com

Kehinde Wiley made me fall in love with art again. He made me feel powerful and seen. I grew up drawing, loved to draw, and took several art history and anatomy courses in college. Creating an entire world on a piece of paper, canvas, or in photoshop is something that I can get entirely lost in. It started when my mom gave me my first light-up desk at age 7. I would use it to trace Archie comics & anything of interest that I could get my hands on. As a teenager, like Kehinde, I was inspired by the Masters (the white ones that I was exposed to). I’d copy pieces from the masters and my favorite comic book Gen13. I started off with pointillism and Van Gogh, then graduated to surrealism. Salvador Dahli & Edward Hopper became minor obsessions of mine. I loved the melancholy & unsettling nature of surrealism. I loved the isolation and stillness in Hopper’s pieces & to this day, Hopper’s world represents the ideal place I’d like to live in except maybe on a beach in the Caribbean instead of a lonely theatre somewhere in North America.

Throughout all the works of art that I’ve loved from Van Gogh to Lucien Freud, I never came across artists or subjects that looked like me.

One of my favorite American artists, Norman Rockwell, most known for his piece titled “The Problem We All Live With” which depicted a six year old Ruby Bridges being escorted by US Marshalls on her first day of integrating the William Frantz Public School in New Orleans on November 14, 1960, was censored for a great deal of his career.

“In an interview later in his life, Rockwell recalled having been directed to paint out a black person out of a group picture because the "Saturday Evening Post" policy at that time allowed showing black people only in service industry jobs. Having left the "Post" in 1963, Rockwell was free from such restraints and seemed eager to correct prejudices inadvertently reflected in previous work.”

“Sharrod Hosten Study IV,” 2010. Artwork by Kehinde Wiley

Credit: kehindewiley.com

Whether it’s the works of the European masters in the mid 17th century, lynching photography in America in the early 1900’s, or Kodak’s, Shirley card, the message is that blacks are only supposed to occupy certain spaces. Wiley is breaking some of the chains that bind us and allowing us to step into different roles; roles that we have long occupied but have been erased from the narrative of black life in America. His presence and success reminds us that we should have the right to tell our own stories, to unapologetically be our full selves. Kehinde Wiley is a reminder that we have always been a part of the art world and we deserve to be there. He is a reminder that despite the odds being stacked against us, still we rise. It’s full time for a change of guard in the art world and I look forward to seeing works from many different masters from a variety of different ethnic backgrounds telling their own stories on the canvas and behind the scenes.

Credit: Abdoulaye N'dao for The New York Times